NDT Training On Magnetic Particle Testing

Magnetic particle testing is one of the most widely utilized NDT methods since it is fast and relatively easy to apply and part surface preparation is not as critical as it is for some other methods. This method uses magnetic fields and small magnetic particles (i.e.iron filings) to detect flaws in components. The only requirement from an inspectability standpoint is that the component being inspected must be made of a ferromagnetic material (a materials that can be magnetized) such as iron, nickel, cobalt, or some of their alloys.

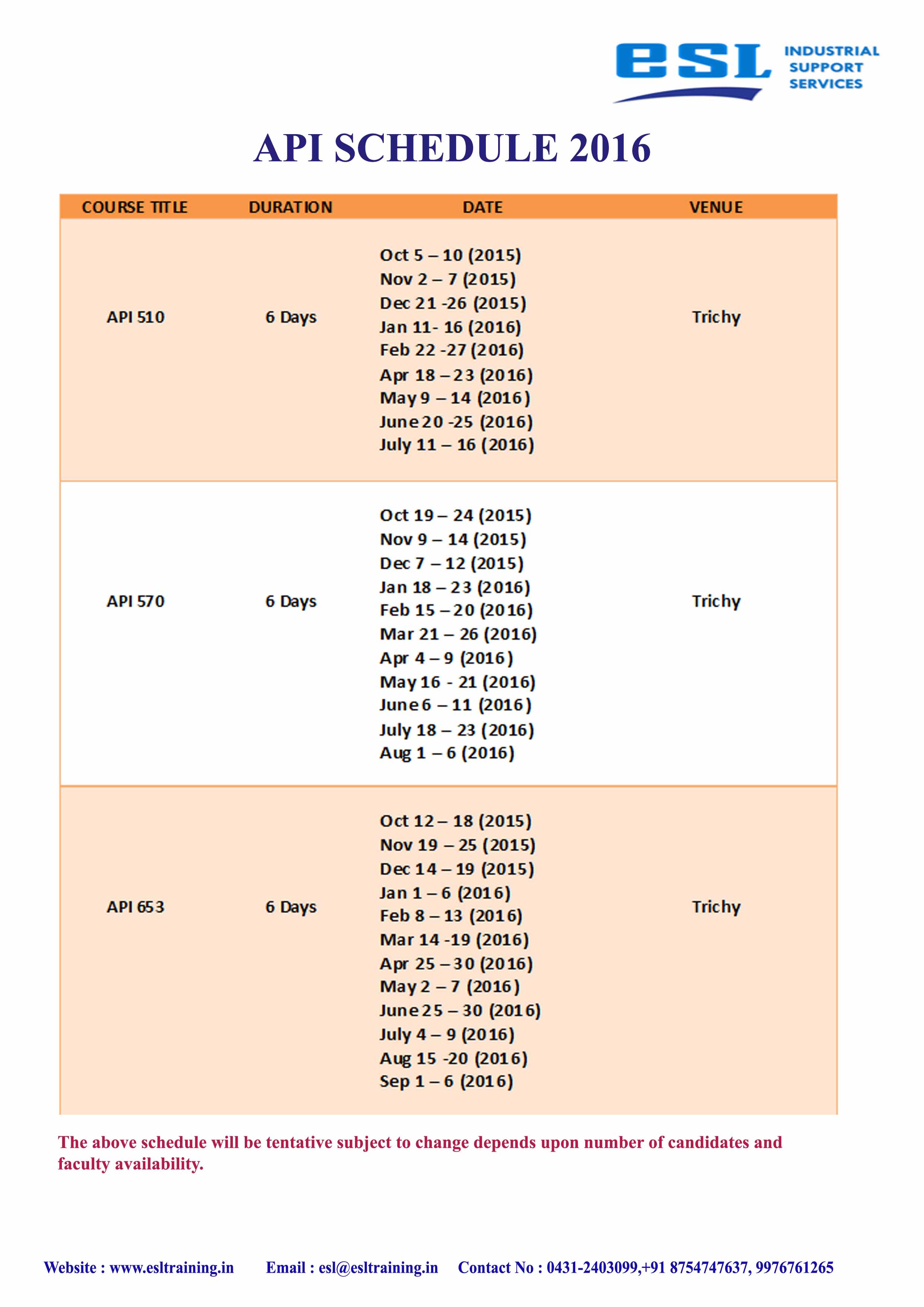

The method is used to inspect a variety of product forms including castings, forgings, and weldments. Many different industries use magnetic particle inspection such as structural steel, automotive, petrochemical, power generation, and aerospace industries. Underwater inspection is another area where magnetic particle inspection may be used to test items such as offshore structures and underwater pipelines.

magnetic particle testing

Basic Principles Magnetic particle testing

In theory,

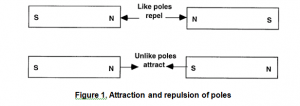

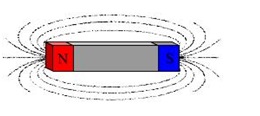

magnetic particle testing has a relatively simple concept. It can be considered as a combination of two nondestructive testing methods: magnetic flux leakage testing and visual testing. For the case of a bar magnet, the magnetic field is in and around the magnet. Any place that a magnetic line of force exits or enters the magnet is called a “pole” (magnetic lines of force exit the magnet from north pole and enter from the south pole).

When a bar magnet is broken in the center of its length, two complete bar magnets with magnetic poles on each end of each piece will result. If the magnet is just cracked but not broken completely in two, a north and south pole will form at each edge of the crack. The magnetic field exits the north pole and reenters at the south pole. The magnetic field spreads out when it encounters the

small air gap created by the crack because the air cannot support as much magnetic field per unit volume as the magnet can. When the field spreads out, it appears to leak out of the material and, thus is called a flux leakage field.

If iron particles are sprinkled on a cracked magnet, the particles will be attracted to and cluster not only at the poles at the ends of the magnet, but also at the poles at the edges of the crack. This cluster of particles is much easier to see than the actual crack and this is the basis for magnetic particle inspection.

The first step in a magnetic particle testing is to magnetize the component that is to be inspected. If any defects on or near the surface are present, the defects will create a leakage field. After the component has been magnetized, iron particles, either in a dry or wet suspended form, are applied to the surface of the magnetized part. The particles will be attracted and cluster at the flux leakage fields, thus forming a visible indication that the inspector can detect.

magnetic particle testing

Advantages and Disadvantages

The primary advantages and disadvantages when compared to other NDT methods are:

Advantages

- High sensitivity (small discontinuities can be detected).

- Indications are produced directly on the surface of the part and constitute a visual representation of the flaw.

- Minimal surface preparation (no need for paint removal)

- Portable (small portable equipment & materials available in spray cans)

- Low cost (materials and associated equipment are relatively inexpensive)

Disadvantages

- Only surface and near surface defects can be detected.

- Only applicable to ferromagnetic materials.

- Relatively small area can be inspected at a time.

- Only materials with a relatively nonporous surface can be inspected.

- The inspector must have direct access to the surface being inspected.

Magnetism

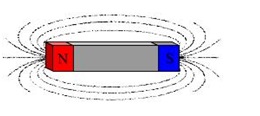

The concept of magnetism centers around the magnetic field and what is known as a dipole. The term “magnetic field” simply describes a volume of space where there is a change in energy within that volume. The location where a magnetic field exits or enters a material is called a magnetic pole. Magnetic poles have never been detected in isolation but always occur in pairs, hence the name dipole. Therefore, a dipole is an object that has a magnetic pole on one end and a second, equal but opposite, magnetic pole on the other. A bar magnet is a dipole with a north pole at one end and south pole at the other.

The source of magnetism lies in the basic building block of all matter, the atom. Atoms are composed of protons, neutrons and electrons. The protons and neutrons are located in the atom’s nucleus and the electrons are in constant motion around the nucleus. Electrons carry a negative electrical charge and produce a magnetic field as they move through space. A magnetic field is produced whenever an electrical charge is in motion. The strength of this field is called the magnetic moment.

When an electric current flows through a conductor, the movement of electrons through the conductor causes a magnetic field to form around the conductor. The magnetic field can be detected using a compass. Since all matter is comprised of atoms, all materials are affected in some way by a magnetic field; however, materials do not react the same way to the magnetic field.

Reaction of Materials to Magnetic Field

When a material is placed within a magnetic field, the magnetic forces of the material’s electrons will be affected. This effect is known as Faraday’s Law of Magnetic Induction. However, materials can react quite differently to the presence of an external magnetic field. The magnetic moments associated with atoms have three origins: the electron motion, the change in motion caused by an external magnetic field, and the spin of the electrons.

In most atoms, electrons occur in pairs where these pairs spin in opposite directions. The opposite spin directions of electron pairs cause their magnetic fields to cancel each other. Therefore, no net magnetic field exists. Alternately, materials with some unpaired electrons will have a net magnetic field and will react more to an external field.According to their interaction with a magnetic field, materials can be classified as:

Diamagnetic materials: which have a weak, negative susceptibility to magnetic fields. Diamagnetic materials are slightly repelled by a magnetic field and the material does not retain the magnetic properties when the external field is removed. In diamagnetic materials all the electrons are paired so there is no permanent net magnetic moment per atom. Most elements in the periodic table, including copper, silver, and gold, are diamagnetic.

Paramagnetic materials: which have a small, positive susceptibility to magnetic fields. These materials are slightly attracted by a magnetic field and the material does not retain the magnetic properties when the external field is removed.

Paramagnetic materials have some unpaired electrons. Examples of paramagnetic materials include magnesium, molybdenum, and lithium.

Ferromagnetic materials: have a large, positive susceptibility to an external magnetic field. They exhibit a strong attraction to magnetic fields and are able to retain their magnetic properties after the external field has been removed. Ferromagnetic materials have some unpaired electrons so their atoms have a net magnetic moment. They get their strong magnetic properties due to the presence of magnetic domains. In these domains, large numbers of atom’s moments are aligned parallel so that the magnetic force within the domain is strong (this happens during the solidification of the material where the atom moments are aligned within each crystal ”i.e., grain” causing a strong magnetic force in one direction). When a ferromagnetic material is in the

unmagnetized state, the domains are nearly randomly organized (since the crystals are in arbitrary directions) and the net magnetic field for the part as a whole is zero. When a magnetizing force is applied, the domains become aligned to produce a strong magnetic field within the part. Iron, nickel, and cobalt are examples of ferromagnetic materials. Components made of these materials are commonly inspected using the magnetic particle method.

Magnetic Field Characteristics

Magnetic Field In and Around a Bar Magnet

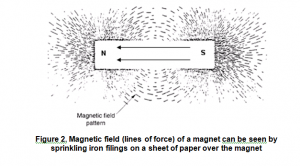

The magnetic field surrounding a bar magnet can be seen in the magnetograph below. A magnetograph can be created by placing a piece

of paper over a magnet and sprinkling the paper with iron filings. The particles align themselves with the lines of magnetic force produced by the magnet. It can be seen in the magnetograph that there are poles all along the length of the magnet but that the poles are concentrated at the ends of the magnet (the north and south poles).

Magnetic Fields in and around Horseshoe and Ring Magnets

Magnets come in a variety of shapes and one of the more common is the horseshoe (U) magnet. The horseshoe magnet has north and south poles just like a bar magnet but the magnet is curved so the poles lie in the same plane. The magnetic lines of force flow from pole to pole just like in the bar magnet. However, since the poles are located closer together and a more direct path exists for the lines of flux to travel between the poles, the magnetic field is concentrated between the poles.

General Properties of Magnetic Lines of Force

Magnetic lines of force have a number of important properties, which include:

- They seek the path of least resistance between opposite magnetic poles (in a single bar magnet shown, they attempt to form closed loops from pole to pole).

- They never cross one another.

- They all have the same strength.

- Their density decreases with increasing distance from the poles.

- Their density decreases (they spread out) when they move from an area of higher permeability to an area of lower permeability.

- They are considered to have direction as if flowing, though no actual movement occurs.

- They flow from the south pole to the north pole within a material and north pole to south pole in air.

Electromagnetic Fields

Magnets are not the only source of magnetic fields. The flow of electric current through a conductor generates a magnetic field. When electric current flows in a long straight wire, a circular magnetic field is generated around the wire and the intensity of this magnetic field is directly proportional to the amount of current

carried by the wire. The strength of the field is strongest next to the wire and diminishes with distance. In most conductors, the magnetic field exists only as long as the current is flowing.

However, in ferromagnetic materials the electric current will cause some or all of the magnetic domains to align and a residual magnetic field will remain.

Also, the direction of the magnetic field is dependent on the direction of the electrical current in the wire. The direction of the magnetic field around a conductor can be determined using a simple rule called the “right-hand clasp rule”. If a person grasps a conductor in one’s right hand with the thumb pointing in the direction of the current, the fingers will circle the conductor in the direction of the magnetic field.

Note: remember that current flows from the positive terminal to the negative terminal (electrons flow in the opposite direction).

Magnetic Field Produced by a Coil

When a current carrying wire is formed into several loops to form a coil, the magnetic field circling each loop combines with the fields from the other loops to produce a concentrated field through the center of the coil (the field flows along the longitudinal axis and circles back around the outside of the coil).

When the coil loops are tightly wound, a uniform magnetic field is developed throughout the length of the coil. The strength of the magnetic field increases not only with increasing current but also with each loop that is added to the coil. A long, straight coil of wire is called a solenoid and it can be used to generate a nearly uniform magnetic field similar to that of a bar magnet. The concentrated magnetic field inside a coil is very useful in magnetizing ferromagnetic materials for inspection using the magnetic particle testing method.

Quantifying Magnetic Properties

The various characteristics of magnetism can be measured and expressed quantitatively. Different systems of units can be used for quantifying magnetic properties. SI units will be used in this material. The advantage of using SI units is that they are traceable back to an agreed set of four base units; meter, kilogram, second, and Ampere.

- The unit for magnetic field strength H is ampere/meter (A/m). A magnetic field strength of 1 A/m is produced at the center of a single circular conductor with a 1 meter diameter carrying a steady current of 1 ampere.

- The number of magnetic lines of force cutting through a plane of a given area at a right angle is known as the magnetic flux density, B. The flux density or magnetic induction has the Tesla as its unit. One Tesla is equal to 1 Newton/(A/m). From these units, it can be seen that the flux density is a measure of the force applied to a particle by the magnetic field.

- The total number of lines of magnetic force in a material is called magnetic flux, ɸ. The strength of the flux is determined by the number of magnetic domains

that are aligned within a material. The total flux is simply the flux density applied over an area. Flux carries the unit of a weber, which is simply a Tesla-meter2.

- The magnetization M is a measure of the extent to which an object is magnetized. It is a measure of the magnetic dipole moment per unit volume of the object. Magnetization carries the same units as a magnetic field A/m.

|

Quantity |

|

SI Units |

SI Units |

CGS Units |

|

|

|

(Sommerfeld) |

(Kennelly) |

(Gaussian) |

|

Field |

H |

A/m |

A/m |

oersteds |

|

(Magnetization |

|

|

|

|

|

Force) |

|

|

|

|

|

Flux Density |

B |

Tesla |

Tesla |

gauss |

|

(Magnetic |

|

|

|

|

|

Induction) |

|

|

|

|

|

Flux |

ɸ |

Weber |

Weber |

maxwell |

|

Magnetization |

M |

A/m |

– |

erg/Oe-cm3 |

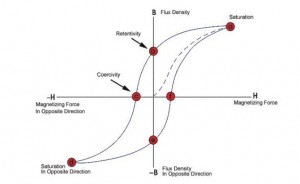

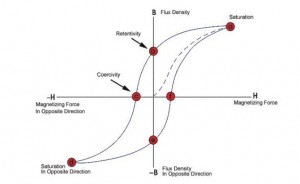

The Hysteresis Loop and Magnetic Properties

A great deal of information can be learned about the magnetic properties of a material by studying its hysteresis loop. A hysteresis loop shows the relationship between the induced magnetic flux density (B) and the magnetizing force (H). It is often referred to as the B-H loop. An example hysteresis loop is shown below.

magnetic particle testing

The loop is generated by measuring the magnetic flux of a ferromagnetic material while the magnetizing force is changed. A ferromagnetic material that has never been previously magnetized or has been thoroughly demagnetized will follow the dashed line as H is increased. As the line demonstrates, the greater the amount of current applied (H+), the stronger the magnetic field in the component (B+). At point “a”

almost all of the magnetic domains are aligned and an additional increase in the magnetizing force will produce very little increase in magnetic flux. The material has reached the point of magnetic saturation. When H is reduced to zero, the curve will move from point “a” to point “b“. At this point, it can be seen that some magnetic flux remains in the material even though the magnetizing force is zero. This is referred to as the point of retentivity on the graph and indicates the level of residual magnetism in the material (Some of the magnetic domains remain aligned but some have lost their alignment). As the magnetizing force is reversed, the curve moves to point “c“, where the flux has been reduced to zero. This is called the point of coercivity on the curve (the reversed magnetizing force has flipped enough of the domains so that the net flux within the material is zero). The force required to remove the residual magnetism from the material is called the coercive force or coercivity of the material.

As the magnetizing force is increased in the negative direction, the material will again become magnetically saturated but in the opposite direction, point “d“. Reducing H to zero brings the curve to point “e“. It will have a level of residual magnetism equal to that achieved in the other direction. Increasing H back in the positive direction will return B to zero. Notice that the curve did not return to the origin of the graph because some force is required to remove the residual magnetism. The curve will take a different path from point “f” back to the saturation point where it with complete the loop.

From the hysteresis loop, a number of primary magnetic properties of a material can be determined:

- Retentivity – A measure of the residual flux density corresponding to the saturation induction of a magnetic material. In other words, it is a material’s ability to retain a certain amount of residual magnetic field when the magnetizing force is removed after achieving saturation (The value of B at point b on the hysteresis curve).

- Residual Magnetism or Residual Flux – The magnetic flux density that remains in a material when the magnetizing force is zero. Note that residual magnetism and retentivity are the same when the material has been magnetized to the saturation point. However, the level of residual magnetism may be lower than the retentivity value when the magnetizing force did not reach the saturation level.

- Coercive Force – The amount of reverse magnetic field which must be applied to a magnetic material to make the magnetic flux return to zero (The value of H at point c on the hysteresis curve).

- Permeability, µ – A property of a material that describes the ease with which a magnetic flux is established in the material.

- Reluctance – Is the opposition that a ferromagnetic material shows to the establishment of a magnetic field. Reluctance is analogous to the resistance in an electrical circuit.

Permeability

As previously mentioned, permeability (µ) is a material property that describes the ease with which a magnetic flux is established in a component. It is the ratio of the flux density (B) created within a material to the magnetizing field (H) and is represented by the following equation:

µ = B/H

This equation describes the slope of the curve at any point on the hysteresis loop. The permeability value given in letrature for materials is usually the maximum permeability or the maximum relative permeability. The maximum permeability is the point where the slope of the B/H curve for the unmagnetized material is the greatest. This point is often taken as the point where a straight line from the origin is tangent to the B/H curve.

The shape of the hysteresis loop tells a great deal about the material being magnetized. The hysteresis curves of two different materials are shown in the graph.

- Relative to other materials, a material with a wider hysteresis loop has:

- Lower Permeability

- Higher Retentivity

- Higher Coercivity

- Higher Residual Magnetism

- Relative to other materials, a material with a narrower hysteresis loop has:

- Higher Permeability

- Lower Retentivity

- Lower Coercivity

- Lower Reluctance

– Lower Residual Magnetism

In magnetic particle testing, the level of residual magnetism is important. Residual magnetic fields are affected by the permeability, which can be related to the carbon content and alloying of the material. A component with high carbon content will have low permeability and will retain more magnetic flux than a material with low carbon content.

Magnetic Field Orientation and Flaw Detectability

To properly inspect a component for cracks or other defects, it is important to understand that the orientation of the crack relative to the magnetic lines of force determinies if the crack can or cannot be detected. There are two general types of magnetic fields that can be established within a component.

- A longitudinal magnetic field has magnetic lines of force that run parallel to the long axis of the part. Longitudinal magnetization of a component can be accomplished using the longitudinal field set up by a coil or solenoid. It can also be accomplished using permanent magnets or electromagnets.

- A circular magnetic field has magnetic lines of force that run circumferentially around the perimeter of a part. A circular magnetic field is induced in an article by either passing current through the component or by passing current through a conductor surrounded by the component.

The type of magnetic field established is determined by the method used to magnetize the specimen. Being able to magnetize the part in two directions is important because the best detection of defects occurs when the lines of magnetic force are established at right angles to the longest dimension of the defect. This

orientation creates the largest disruption of the magnetic field

within the part and the greatest flux leakage at the surface of the part. If the magnetic field is parallel to the defect, the field will see little disruption and no flux leakage field will be produced.

An orientation of 45 to 90 degrees between the magnetic field and the defect is necessary to form an indication. Since defects may occur in various and unknown directions, each part is normally magnetized in two directions at right angles to each other. If the component shown is considered, it is known that passing current through the part from end to end will establish a circular magnetic field that will be 90 degrees to the direction of the current.

Therefore, defects that have a significant dimension in the direction of the current (longitudinal defects) should be detectable, while transverse-type defects will not be detectable with circular magnetization.

Magnetization of Ferromagnetic Materials

There are a variety of methods that can be used to establish a magnetic field in a component for evaluation using magnetic particle inspection. It is common to classify the magnetizing methods as either direct or indirect.

Magnetization Using Direct Induction (Direct Magnetization)

With direct magnetization, current is passed directly through the component. The flow of current causes a circular magnetic field to form in and around the conductor. When using the direct magnetization method, care must be taken to ensure that good electrical contact is established and maintained between the test equipment and the test component to avoid damage of the the component (due to arcing or overheating at high resistance ponts).

There are several ways that direct magnetization is commonly accomplished.

- One way involves clamping the component between two electrical contacts in a special piece of equipment. Current is passed through the component and a circular magnetic field is established in and around the component. When the magnetizing current is stopped, a residual magnetic field will remain within the component. The strength of the induced magnetic field is proportional to the amount of current passed through the component.

- A second technique involves using clamps or prods, which are attached or placed in contact with the component. Electrical current flows through the component from contact to contact. The current sets up a circular magnetic field around the path of the current.

Magnetization Using Indirect Induction (Indirect Magnetization)

Indirect magnetization is accomplished by using a strong external magnetic field to establish a magnetic field within the component. As with direct magnetization, there are several ways that indirect magnetization can be accomplished.

- The use of permanent magnets is a low cost method of establishing a magnetic field. However, their use is limited due to lack of control of the field strength and the difficulty of placing and removing strong permanent magnets from the component.

- Electromagnets in the form of an adjustable horseshoe magnet (called a yoke) eliminate the problems associated with permanent magnets and are used extensively in industry. Electromagnets only exhibit a magnetic flux when electric current is flowing around the soft iron core. When the magnet is placed on the component, a magnetic field is established between the north and south poles of the magnet.

- Another way of indirectly inducting a magnetic field in a material is by using the magnetic field of a current carrying conductor. A circular magnetic field can be established in cylindrical components by using a central conductor. Typically, one or more cylindrical components are hung from a solid copper bar running through the inside diameter. Current is passed through the copper bar and the resulting circular magnetic field establishes a magnetic field within the test components.

- The use of coils and solenoids is a third method of indirect magnetization. When the length of a component is several times larger than its diameter, a longitudinal

magnetic field can be established in the component. The component is placed longitudinally in the concentrated magnetic field that fills the center of a coil or solenoid. This magnetization technique is often referred to as a “coil shot“.

Types of Magnetizing Current

As mentioned previously, electric current is often used to establish the magnetic field in components during magnetic particle inspection. Alternating current (AC) and direct current (DC) are the two basic types of current commonly used. The type of current used can have an effect on the inspection results, so the types of currents commonly used are briefly discussed here.

Direct Current

Direct current (DC) flows continuously in one direction at a constant voltage. A battery is the most common source of direct current. The current is said to flow from the positive to the negative terminal, though electrons flow in the opposite direction. DC is very desirable when inspecting for subsurface defects because DC generates a magnetic field that penetrates deeper into the material. In ferromagnetic materials, the magnetic field produced by DC generally penetrates the entire cross-section of the component.

Alternating Current

Alternating current (AC) reverses in direction at a rate of 50 or 60 cycles per second. Since AC is readily available in most facilities, it is convenient to make use of it for magnetic particle inspection. However, when AC is used to induce a magnetic field in ferromagnetic materials, the magnetic field will be limited to a thin layer at the surface of the component. This phenomenon is known as the “skin effect” and it occurs because the changing magnetic field generates eddy currents in the test object. The eddy currents produce a magnetic field that opposes the primary field, thus reducing the net magnetic flux below the surface. Therefore, it is recommended that AC be used only when the inspection is limited to surface defects.

Rectified Alternating Current

Clearly, the skin effect limits the use of AC since many inspection applications call for the detection of subsurface defects. Luckily, AC can be converted to current that is very much like DC through the process of rectification. With the use of rectifiers, the reversing AC can be converted to a one directional current. The three commonly used types of rectified current are described below.

Half Wave Rectified Alternating Current (HWAC)

When single phase alternating current is passed through a rectifier, current is allowed to flow in only one direction. The reverse half of each cycle is blocked out so that a one directional, pulsating current is produced. The current rises from zero to a maximum and then returns to zero. No current flows during the time when the reverse cycle is blocked out. The HWAC repeats at same rate as the unrectified current (50 or 60 Hz). Since half of the current is blocked out, the amperage is half of the unaltered AC. This type of current is often referred to as half wave DC or pulsating DC. The pulsation of the HWAC helps in forming magnetic particle indications by vibrating the particles and giving them added mobility where that is especially important when using dry particles. HWAC is most often used to power electromagnetic yokes.

Full Wave Rectified Alternating Current (FWAC) (Single Phase)

Full wave rectification inverts the negative current to positive current rather than blocking it out. This produces a pulsating DC with no interval between the pulses. Filtering is usually performed to soften the sharp polarity switching in the rectified current. While particle mobility is not as good as half-wave AC due to the reduction in pulsation, the depth of the subsurface magnetic field is improved.

Three Phase Full Wave Rectified Alternating Current

Three phase current is often used to power industrial equipment because it has more favorable power transmission and line loading characteristics. This type of electrical current is also highly desirable for magnetic particle testing because when it is rectified and filtered, the resulting current very closely resembles direct current. Stationary magnetic particle equipment wired with three phase AC will usually have the ability to magnetize with AC or DC (three phase full wave rectified), providing the inspector with the advantages of each current form.

Magnetic Fields Distribution and Intensity

Longitudinal Fields

When a long component is magnetized using a solenoid having a shorter length, only the material within the solenoid and

about the same length on each side of the solenoid will be strongly magnetized. This occurs because the magnetizing force diminishes with increasing distance from the solenoid. Therefore, a long component must be magnetized and inspected at several locations along its length for complete inspection coverage.

Circular Fields

When a circular magnetic field is forms in and around a conductor due to the passage of electric current through it, the following can be said about the distribution and intensity of the magnetic field:

- The field strength varies from zero at the center of the component to a maximum at the surface.

- The field strength at the surface of the conductor decreases as the radius of the conductor increases (when the current strength is held constant).

- The field strength inside the conductor is dependent on the current strength, magnetic permeability of the material, and if magnetic, the location on the B-H curve.

- The field strength outside the conductor is directly proportional to the current strength and it decreases with distance from the conductor.

The images below show the magnetic field strength graphed versus distance from the center of the conductor when current passes through a solid circular conductor.

- In a nonmagnetic conductor carrying DC, the internal field strength rises from zero at the center to a maximum value at the surface of the conductor.

- In a magnetic conductor carrying DC, the field strength within the conductor is much greater than it is in the nonmagnetic conductor. This is due to the permeability of the magnetic material. The external field is exactly the same for the two materials provided the current level and conductor radius are the same.

- When the magnetic conductor is carrying AC, the internal magnetic field will be concentrated in a thin layer near the surface of the conductor (skin effect). The external field decreases with increasing distance from the surface same as with DC.

The magnetic field distribution in and around a solid conductor of a nonmagnetic material carrying direct current.In a hollow circular conductor there is no magnetic field in the void area. The magnetic field is zero at the inner surface and rises until it reaches a maximum at the outer surface.

- Same as with a solid conductor, when DC current is passed through a magnetic conductor, the field strength within the conductor is much greater than in nonmagnetic conductor due to the permeability of the magnetic material. The external field strength decreases with distance from the surface of the conductor. The external field is exactly the same for the two materials provided the current level and conductor radius are the same.

- When AC current is passed through a hollow circular magnetic conductor, the skin effect concentrates the magnetic field at the outside diameter of the component.

The magnetic field distribution in and around a hollow conductor of a nonmagnetic material carrying direct current.

As can be seen from these three field distribution images, the field strength at the inside surface of hollow conductor is very low when a circular magnetic field is established by direct magnetization. Therefore, the direct method of magnetization is not recommended when inspecting the inside diameter wall of a hollow component for shallow defects (if the defect has significant depth, it may be detectable using DC since the field strength increases rapidly as one moves from the inner towards the outer surface).

- A much better method of magnetizing hollow components for inspection of the ID and OD surfaces is with the use of a central conductor. As can be seen in the field distribution image, when current is passed through a nonmagnetic central conductor (copper bar), the magnetic field produced on the inside diameter surface of a magnetic tube is much greater and the field is still strong enough for defect detection on the OD surface.

Demagnetization

After conducting a magnetic particle inspection, it is usually necessary to demagnetize the component. Remanent magnetic fields can:

- affect machining by causing cuttings to cling to a component.

- interfere with electronic equipment such as a compass.

- create a condition known as “arc blow” in the welding process. Arc blow may cause the weld arc to wonder or filler metal to be repelled from the weld.

- cause abrasive particles to cling to bearing or faying surfaces and increase wear.

Removal of a field may be accomplished in several ways. The most effective way to demagnetize a material is by heating the material above its curie temperature (for instance, the curie temperature for a low carbon steel is 770°C). When steel is heated above its curie temperature then it is cooled back down, the the orientation of the magnetic domains of the individual grains will become randomized again and thus the component will contain no residual magnetic field. The material should also be placed with it long axis in an east-west orientation to avoid any influence of the Earth’s magnetic field.

However, it is often inconvenient to heat a material above its curie temperature to demagnetize it, so another method that returns the material to a nearly unmagnetized state is commonly used.

Subjecting the component to a reversing and decreasing magnetic field will return the dipoles to a nearly random orientation throughout the material. This can be accomplished by pulling a component out and away from a coil with AC passingthrough it. With AC Yokes, demagnetization of local areas may be accomplished by placing the yoke contacts on the surface, moving them in circular patterns around the area, and slowly withdrawing the yoke while the current is applied. Also, many stationary magnetic particle inspection units come with a demagnetization feature that slowly reduces the AC in a coil in which the component is placed.

A field meter is often used to verify that the residual flux has been removed from a component. Industry standards usually require that the magnetic flux be reduced to less than 3 Gauss (3×10-4 Tesla) after completing a magnetic particle inspection.

Measuring Magnetic Fields

When performing a magnetic particle inspection, it is very important to be able to determine the direction and intensity of the magnetic field. The field intensity must be high enough to cause an indication to form, but not too high to cause nonrelevant indications to mask relevant indications. Also, after magnetic inspection it is often needed to measure the level of residual magnetezm.

Since it is impractical to measure the actual field strength within the material, all the devices measure the magnetic field that is outside of the material. The two devices commonly used for quantitative measurement of magnetic fields n magnetic particle inspection are the field indicator and the Hall-effect meter, which is also called a gauss meter.

Field Indicators

Field indicators are small mechanical devices that utilize a soft iron vane that is deflected by a magnetic field. The vane is attached to a needle that rotates and moves the pointer for the scale. Field indicators can be adjusted and calibrated so that quantitative information can be obtained. However, the measurement range of field indicators is usually small due to the mechanics of the device (the one shown in the image has a range from plus 20 to minus 20 Gauss). This limited range makes them best suited for measuring the residual magnetic field after demagnetization.

Hall-Effect (Gauss/Tesla) Meter

A Hall-effect meter is an electronic device that provides a digital readout of the magnetic field strength in Gauss or Tesla units. The meter uses a very small conductor or semiconductor element at the tip of the probe. Electric

current is passed through the conductor. In a magnetic field, a force is exerted on the moving electrons which tends to push them to one side of the conductor. A buildup of charge at the sides of the conductors will balance this magnetic influence, producing a measurable voltage between the two sides of the conductor. The probe is placed in the magnetic field such that the magnetic lines of force intersect the major dimensions of the sensing element at a right angle.

Magnetization Equipment for Magnetic Particle Testing

To properly inspect a part for cracks or other defects, it is important to become familiar with the different types of magnetic fields and the equipment used to generate them. As discussed previously, one of the primary requirements for detecting a defect in a ferromagnetic material is that the magnetic field induced in the part must intercept the defect at a 45 to 90 degree angle. Flaws that are normal (90 degrees) to the magnetic field will produce the strongest indications because they disrupt more of the magnet flux. Therefore, for proper inspection of a component, it is important to be able to establish a magnetic field in at least two directions.

A variety of equipment exists to establish the magnetic field for magnetic particle testing. One way to classify equipment is based on its portability. Some equipment is designed to be portable so that inspections can be made in the field and some is designed to be stationary for ease of inspection in the laboratory or manufacturing facility.

Portable Equipment

Permanent Magnets

Permanent magnets can be used for magnetic particle inspection as the source of magnetism (bar magnets or horseshoe magnets). The use of industrial magnets is not popular because they are very strong (they require significant strength to remove them

from the surface, about 250 N for some magnets) and thus they are difficult and sometimes dangerous to handle. However, permanent magnets are sometimes used by divers for inspection in underwater environments or other areas, such as explosive environments, where electromagnets cannot be used. Permanent magnets can also be made small enough to fit into tight areas where electromagnets might not fit.

Electromagnetic Yokes

An electromagnetic yoke is a very common piece of equipment that is used to establish a magnetic field. A switch is included in the electrical circuit so that the current and, therefore, the magnetic field can be turned on

and off. They can be powered with AC from a wall socket or by DC from a battery pack. This type of magnet generates a very strong magnetic field in a local area where the poles of the magnet touch the part being inspected. Some yokes can lift weights in excess of 40 pounds.

Prods

Prods are handheld electrodes that are pressed against the surface of the component being inspected to make contact for passing electrical current (AC or DC) through the metal. Prods are typically made from copper and have an insulated handle to help protect the operator. One of the prods has a trigger switch so that the current can be quickly and easily turned on and off. Sometimes the two prods are connected by any insulator, as shown in the image, to facilitate one hand operation. This is referred to as a dual prod and is commonly used for weld inspections.

However, caution is required when using prods because electrical arcing can occur and cause damage to the component if proper contact is not maintained between the prods and the component surface. For this reason, the use of prods is not allowed when inspecting aerospace and other critical components. To help prevent arcing, the prod tips should be inspected frequently to ensure that they are not oxidized, covered with scale or other contaminant, or damaged.

Portable Coils and Conductive Cables

Coils and conductive cables are used to establish a longitudinal magnetic field within a component. When a preformed coil is used, the component is placed against the inside surface on the coil. Coils typically have three or five turns of a copper cable within the molded frame. A foot switch is often used to energize the coil.

Also, flexible conductive cables can be wrapped around a component to form a coil. The number of wraps is determined by the magnetizing force needed and of course, the length of the cable. Normally, the wraps are kept as close together as possible. When using a coil or cable wrapped into a coil, amperage is usually expressed in ampere-turns. Ampere-turns is the amperage shown on the amp meter times the number of turns in the coil.

Portable Power Supplies

Portable power supplies are used to provide the necessary electricity to the prods, coils or cables. Power supplies are commercially available in a variety of sizes. Small power supplies generally provide up to 1,500A of half-wave DC or AC. They are small and light enough to be carried and operate on either 120V or 240V electrical service.

When more power is necessary, mobile power supplies can be used. These units come with wheels so that they can be rolled where needed. These units also operate on 120V or 240V electrical service and can provide up to 6,000A of AC or half-wave DC.

Stationery Equipment

Stationary magnetic particle inspection equipment is designed for use in laboratory or production environment. The most common stationary system is the wet horizontal (bench) unit. Wet horizontal units are designed to allow for batch inspections of a variety of components. The units have head and tail stocks (similar to a lathe) with electrical contact that the part can be clamped between. A circular magnetic field is produced with direct magnetization.

Most units also have a movable coil that can be moved into place so the indirect magnetization can be used to produce a longitudinal magnetic field. Most coils have five turns and can be obtained in a variety of sizes. The wet magnetic particle solution is collected and held in a tank. A pump and hose system is used to apply the particle solution to the components being inspected. Some of the systems offer a variety of options in electrical current used for magnetizing the component (AC, half wave DC, or full wave DC). In some units, a

demagnetization feature is built in, which uses the coil and decaying AC.

Magnetic Field Indicators

Determining whether a magnetic field is of adequate strength and in the proper direction is critical when performing magnetic particle testing. There is actually no easy-to-apply method that permits an exact measurement of field intensity at a given point within a material. Cutting a small slot or hole into the material and measuring the leakage field that crosses the air gap with a Hall-effect meter is probably the best way to get an estimate of the actual field strength within a part. However, since that is not practical, there are a number of tools and methods that are used to determine the presence and direction of the field surrounding a component.

Hall-Effect Meter (Gauss Meter)

As discussed earlier, a Gauss meter is commonly used to measure the tangential field strength on the surface of the part. By placing the probe next to the surface, the meter measures the intensity of the field in the air adjacent to the component when a magnetic field is applied. The advantages of this device are: it provides a quantitative measure of the strength of magnetizing force tangential to the surface of a test piece, it can be used for measurement of residual magnetic fields, and it can be used repetitively. The main disadvantage is that such devices must be periodically calibrated.

Quantitative Quality Indicator (QQI)

The Quantitative Quality Indicator (QQI) or Artificial Flaw Standard is often the preferred method of assuring proper field direction and adequate field strength (it is used with the wet method only). The QQI is a thin strip (0.05 or 0.1 mm thick) of AISI 1005 steel with a specific pattern, such as concentric circles or a plus sign, etched on it. The QQI is placed directly on the surface, with the itched side facing the surface, and it is usually fixed to the surface using a tape then the component is then magnetized and particles applied. When the field strength is adequate, the particles will adhere over the engraved pattern and provide information about the field direction.

Pie Gage

The pie gage is a disk of highly permeable material divided into four, six, or eight sections by non-ferromagnetic material (such as copper). The divisions serve as artificial defects that radiate out in different directions from the center. The sections are furnace brazed and copper plated. The gage is placed on the test piece copper side up and the test piece is magnetized. After particles are applied and the excess removed, the indications provide the inspector the orientation of the magnetic field. Pie gages are mainly used on flat surfaces such as weldments or steel castings where dry powder is used with a yoke or prods. The pie gage is not recommended for precision parts with complex shapes, for wet-method applications, or for proving field magnitude. The gage should be demagnetized between readings.

Slotted Strips

Slotted strips are pieces of highly permeable ferromagnetic material with slots of different widths. These strips can be used with the wet or dry method. They are placed on the test object as it is inspected. The indications produced on the strips give the inspector a general idea of the field strength in a particular area.

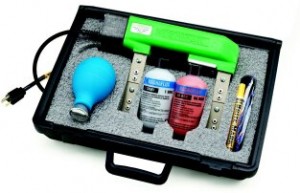

Magnetic Particles

As mentioned previously, the particles that are used for magnetic particle inspection are a key ingredient as they form the indications that alert the inspector to the presence of defects. Particles start out as tiny milled pieces of iron or iron oxide. A pigment (somewhat like paint) is bonded to their surfaces to give the particles color. The metal used for the particles has high magnetic permeability and low retentivity. High magnetic permeability is important because it makes the particles attract easily to small magnetic leakage fields from discontinuities, such as flaws. Low retentivity is important because the particles themselves never become strongly magnetized so they do not stick to each other or the surface of the part. Particles are available in a dry mix or a wet solution.

Dry Magnetic Particles

Dry magnetic particles can typically be purchased in red, black, gray, yellow and several other colors so that a high level of contrast between the particles and the part being inspected can be achieved. The size of the magnetic particles is also very important. Dry magnetic particle products are produced to include a range of particle sizes. The fine particles have a diameter of about 50 µm while the course particles have a diameter of 150 µm (fine particles are more than 20 times lighter than the coarse particles). This makes fine particles more sensitive to the leakage fields from very small discontinuities. However, dry testing particles cannot be made exclusively of the fine particles where coarser particles are needed to bridge large discontinuities and to reduce the powder’s dusty nature. Additionally, small particles easily adhere to surface contamination, such as remnant dirt or moisture, and get

trapped in surface roughness features. It should also be recognized that finer particles will be more easily blown away by the wind; therefore, windy conditions can reduce the sensitivity of an inspection. Also, reclaiming the dry particles is not recommended because the small particles are less likely to be recaptured and the “once used” mix will result in less sensitive inspections.

The particle shape is also important. Long, slender particles tend align themselves along the lines of magnetic force. However, if dry powder consists only of elongated particles, the application process would be less than desirable since long particles lack the ability to flow freely. Therefore, a mix of rounded and elongated particles is used since it results in a dry powder that flows well and maintains good sensitivity. Most dry particle mixes have particles with L/D ratios between one and two.

Wet Magnetic Particles

Magnetic particles are also supplied in a wet suspension such as water or oil. The wet magnetic particle testing method is generally more sensitive than the dry because the suspension provides the particles with more mobility and makes it possible for smaller particles to be used (the particles are typically 10 µm and smaller) since dust and adherence to surface contamination is reduced or eliminated. The wet method also makes it easy to apply the particles uniformly to a relatively large area.

Wet method magnetic particles products differ from dry powder products in a number of ways. One way is that both visible and fluorescent particles are available. Most non-fluorescent particles are ferromagnetic iron oxides, which are either black or brown in color. Fluorescent particles are coated with pigments that fluoresce when exposed to ultraviolet light. Particles that fluoresce green-yellow are most common to take advantage of the peak color sensitivity of the eye but other fluorescent colors are also available.

The carrier solutions can be water or oil-based. Water-based carriers form quicker indications, are generally less expensive, present little or no fire hazard, give off no petrochemical fumes, and are easier to clean from the part. Water-based solutions are usually formulated with a corrosion inhibitor to offer some corrosion protection. However, oil-based carrier solutions offer superior corrosion and hydrogen embrittlement protection to those materials that are prone to attack by these mechanisms.

Also, both visible and fluorescent wet suspended particles are available in aerosol spray cans for increased portability and ease of application.

Dry Particle Inspection

In this magnetic particle testing technique, dry particles are dusted onto the surface of the test object as the item is magnetized. Dry particle inspection is well suited for the inspections conducted on rough surfaces. When an electromagnetic yoke is used, the AC current creates a pulsating magnetic field that provides mobility to the powder.

Dry particle inspection is also used to detect shallow subsurface cracks. Dry particles with half wave DC is the best approach when inspecting for lack of root penetration in welds of thin materials.

Steps for performing dry particles inspection:

- Surface preparation – The surface should be relatively clean but this is not as critical as it is with liquid penetrant inspection. The surface must be free of grease, oil or other moisture that could keep particles from moving freely. A thin layer of paint, rust or scale will reduce test sensitivity but can sometimes be left in place with adequate results. Specifications often allow up to 0.076 mm of a nonconductive coating (such as paint) or 0.025 mm of a ferromagnetic coating (such as nickel) to be left on the surface. Any loose dirt, paint, rust or scale must be removed.

o Some specifications require the surface to be coated with a thin layer of white paint in order to improve the contrast difference between the background and the particles (especially when gray color particles are used).

- Applying the magnetizing force – Use permanent magnets, an electromagnetic yoke, prods, a coil or other means to establish the necessary magnetic flux.

- Applying dry magnetic particles – Dust on a light layer of magnetic particles.

- Blowing off excess powder – With the magnetizing force still applied, remove the excess powder from the surface with a few gentle puffs of dry air. The force of the air needs to be strong enough to remove the excess particles but not strong enough to remove particles held by a magnetic flux leakage field.

- Terminating the magnetizing force – If the magnetic flux is being generated with an electromagnet or an electromagnetic field, the magnetizing force should be terminated. If permanent magnets are being used, they can be left in place.

- Inspection for indications – Look for areas where the magnetic particles are

Wet Suspension Inspection

Wet suspension magnetic particle inspection, more commonly known as wet magnetic particle inspection, involves applying the particles while they are suspended in a liquid carrier. Wet magnetic particle inspection is most commonly performed using a stationary, wet, horizontal inspection unit but suspensions are also available in spray cans for use with an electromagnetic yoke.

A wet inspection has several advantages over a dry inspection. First, all of the surfaces of the component can be quickly and easily covered with a relatively uniform layer of particles. Second, the liquid carrier provides mobility to the particles for an extended period of time, which allows enough particles to float to small leakage fields to form a visible indication. Therefore, wet inspection is considered best for detecting very small discontinuities on smooth surfaces. On rough surfaces, however, the particles (which are much smaller in wet suspensions) can settle in the surface valleys and lose mobility, rendering them less effective than dry powders under these conditions.

Steps for performing wet particle inspection:

- Surface preparation – Just as is required with dry particle inspections, the surface should be relatively clean. The surface must be free of grease, oil and other moisture that could prevent the suspension from wetting the surface and preventing the particles from moving freely. A thin layer of paint, rust or scale will reduce test sensitivity, but can sometimes be left in place with adequate results. Specifications often allow up to 0.076 mm of a nonconductive coating (such as paint) or 0.025 mm of a ferromagnetic coating (such as nickel) to be left on the Any loose dirt, paint, rust or scale must be removed.

o Some specifications require the surface to be coated with a thin layer of white paint when inspecting using visible particles in order to improve the contrast difference between the background and the particles (especially when gray color particles are used).

- Applying suspended magnetic particles – The suspension is gently sprayed or flowed over the surface of the part. Usually, the stream of suspension is diverted from the part just before the magnetizing field is applied.

- Applying the magnetizing force – The magnetizing force should be applied immediately after applying the suspension of magnetic particles. When using a wet horizontal inspection unit, the current is applied in two or three short busts (1/2 second) which helps to improve particle mobility.

- Inspection for indications – Look for areas where the magnetic particles are Surface discontinuities will produce a sharp indication. The indications from subsurface flaws will be less defined and lose definition as depth increases.

Quality & Process Control

Particle Concentration and Condition

Particle Concentration

The concentration of particles in the suspension is a very important parameter and it is checked after the suspension is prepared and regularly monitored as part of the quality system checks. Standards require concentration checks to be performed every eight hours or at every shift change.The standard process used to perform the check requires agitating the carrier for a minimum of thirty minutes to ensure even particle distribution. A sample is then taken in a pear-shaped 100 ml centrifuge tube having a graduated stem (1.0 ml in 0.05 ml increments for fluorescent particles, or 1.5 ml in 0.1 ml increments for visible particles). The sample is then demagnetized so that the particles do not clump together while settling. The sample must then remain undisturbed for a period of time (60 minutes for a petroleum-based carrier or 30 minutes for a water-based carrier). The volume of settled particles is then read. Acceptable ranges are 0.1 to 0.4 ml for fluorescent particles and 1.2 to 2.4 ml for visible particles. If the particle concentration is out of the acceptable range, particles or the carrier must be added to bring the solution back in compliance with the requirement.

Particle Condition After the particles have settled, they should be examined for brightness and agglomeration. Fluorescent particles should be evaluated under ultraviolet light and visible particles under white light. The brightness of the particles should be evaluated weekly by comparing the particles in the test solution to those in an unused reference solution that was saved when the solution was first prepared. Additionally, the particles should appear loose and not lumped together. If the brightness or the agglomeration of the particles is noticeably different from the reference solution, the bath should be replaced.

Suspension Contamination

The suspension solution should also be examined for contamination which may come from inspected components (oils, greases, sand, or dirt) or from the environment (dust). This examination is performed on the carrier and particles collected for concentration testing. Differences in color, layering or banding within the settled particles would indicate contamination. Some contamination is to be expected but if the foreign matter exceeds 30 percent of the settled solids, the solution should be replaced. The liquid carrier portion of the solution should also be inspected for contamination. Oil in a water bath and water in a solvent bath are the primary concerns.

Water Break Test

A daily water break check is required to evaluate the surface wetting performance of water-based carriers. The water break check simply involves flooding a clean surface similar to those being inspected and observing the surface film. If a continuous film forms over the entire surface, sufficient wetting agent is present. If the film of suspension breaks (water break) exposing the surface of the component, insufficient wetting agent is present and the solution should be adjusted or replaced.

Electrical System Checks

Changes in the performance of the electrical system of a magnetic particle inspection unit can obviously have an effect on the sensitivity of an inspection. Therefore, the electrical system must be checked when the equipment is new, when a malfunction is suspected, or every six months. Listed below are the verification tests required by active standards.

Ammeter Check

It is important that the ammeter provide consistent and correct readings. If the meter is reading low, over magnetization will occur and possibly result in excessive background “noise.” If ammeter readings are high, flux density could be too low to produce detectable indications. To verify ammeter accuracy, a calibrated ammeter is connected in series with the output circuit and values are compared to the equipment’s ammeter values. Readings are taken at three output levels in the working range. The equipment meter is not to deviate from the calibrated ammeter more than ±10 percent or 50 amperes, whichever is greater. If the meter is found to be outside this range, the condition must be corrected.

Shot Timer Check

When a timer is used to control the shot duration, the timer must be calibrated. Standards require the timer be calibrated to within ± 0.1 second. A certified timer should be used to verify the equipment timer is within the required tolerances.

Magnetization Strength Check

Ensuring that the magnetization equipment provides sufficient magnetic field strength is essential. Standard require the magnetization strength of electromagnetic yokes to be checked prior to use each day. The magnetization strength is checked by lifting a steel block of a standard weight using the yoke at the maximum pole spacing to be used (10 lb weight for AC yokes or 40 lb weight for DC yokes).

Lighting

Magnetic particle inspection predominately relies on visual inspection to detect any indications that form. Therefore, lighting is a very important element of the inspection process. Obviously, the lighting requirements are different for an inspection conducted using visible particles than they are for an inspection conducted using fluorescent particles.

Light Requirements When Using Visible Particles

Visible particles inspections can be conducted using natural lighting or artificial lighting. However, since natural daylight changes from time to time, the use of artificial lighting is recommended to get better uniformity. Artificial lighting should be white whenever possible (halogen lamps are most commonly used). The light intensity is required to be 100 foot-candles (1076 lux) at the surface being inspected.

Light Requirements When Using Fluorescent Particles

Ultraviolet Lighting

When performing a magnetic particle inspection using fluorescent particles, the condition of the ultraviolet light and the ambient white light must be monitored. Standards and procedures require verification of lens condition and light intensity. Black lights should never be used with a cracked filter as the output of white light and harmful black light will be increased. Also, the cleanliness of the filter should also be checked regularly. The filter should be checked visually and cleaned as necessary before warming-up the light. Most UV light must be warmed up prior to use and should be on for at least 15 minutes before beginning an inspection.

For UV lights used in component evaluations, the normally accepted intensity is 1000 µW/cm2 at 38cm distance from the filter face. The required check should be performed when a new bulb is installed, at startup of the inspection cycle, if a change in intensity is noticed, or every eight hours of continuous use.

Ambient White Lighting

When performing a fluorescent magnetic particle inspection, it is important to keep white light to a minimum as it will significantly reduce the inspector’s ability to detect fluorescent indications. Light levels of less than 2 foot-candles (22 lux) are required by most procedures. When checking black light intensity a reading of the white light produced by the black light may be required to verify white light is being removed by the filter.

White Light for Indication Confirmation

While white light is held to a minimum in fluorescent inspections, procedures may require that indications be evaluated under white light. The white light requirements for this evaluation are the same as when performing an inspection with visible particles. The minimum light intensity at the surface being inspected must be 100 foot-candles (1076 lux).

Light Measurement

Light intensity measurements are made using a radiometer (an instrument that transfers light energy into an electrical current). Some radiometers have the ability to measure both black and white light, while others require a separate sensor for each measurement. Whichever type is used, the sensing area should be clean and free of any materials that could reduce or obstruct light reaching the sensor. Radiometers are relatively unstable instruments and readings often change considerable over time. Therefore, they should be calibrated at least every six months.